Engagement Summary Report - Reducing Violent Crime: A Dialogue on Handguns and Assault-Style Firearms

Hill+Knowlton Strategies (H+K) was retained by Public Safety Canada to provide support in undertaking this engagement project. Public Safety Canada developed the agenda for the in-person roundtables, and selected and invited participants; H+K facilitated these discussions. The online questionnaire was developed and launched by Public Safety Canada. H+K’s role was to analyze and report on data collected through all engagement channels. Public Safety Canada reviewed draft versions of this report and provided H+K with written feedback, which was incorporated into the final product.

Executive Summary

Introduction

Public Safety Canada (“Public Safety”) launched an engagement process in October 2018 to help inform policy, regulations and legislation to reduce violent crime involving firearms. Through this engagement, Public Safety sought to engage and hear from a wide range of stakeholders, which included those both in support of and opposed to limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms. While the engagement was framed by the examination of a potential ban, the discussion explored several potential measures to reduce violent crime.

The engagement process included a series of eight in-person roundtables, an online questionnaire, a written submission process, and bilateral meetings with a range of stakeholders. Given the diversity of perspectives on this issue, this report highlights key common themes and ideas shared by participants, as well as unique and divergent views. The goal of this report is to accurately represent “what we heard” on this issue.

Overall Key Findings

- There are polarized views on a potential ban and limiting access: Overall, participants were strongly polarized on the issue of banning handguns and assault-style firearms. The stakeholder views expressed in two of the engagement channels – the in-person dialogues and written submissions – provided a variety of perspectives both opposed to and in support of a ban. In contrast, most questionnaire respondents (representing a self-selected group of Canadians) were opposed to a ban.

- Target crime and focus on enforcement: Many participants felt strongly that a ban would target law-abiding owners, rather than illicit firearms, and would not greatly impact crime reduction (particularly gang violence). As a result, many called for enhanced enforcement capacity for law enforcement and border services, as well as harsher punishments for firearms trafficking and gun-related crime.

- Address underlying causes of firearm violence: One point of consensus among the diverse perspectives is the need to address the socioeconomic conditions that can lead to gun violence, which requires more support for community-level programs and initiatives. These factors include poverty, a lack of education or employment opportunities, lack of mental health supports and social exclusion.

- Collect and share relevant data on gun crime: There is a need to improve the ongoing collection and sharing of data on gun crime, particularly in terms of sources of illicit firearms and the types of crime being committed. It was expressed that data is critical for supporting law enforcement and border agencies efforts, as well as informing policy and legislation.

- Willingness for collaboration with the firearms community/industry: Many stakeholders representing various aspects of the firearms community want the opportunity to be more engaged and to collaborate with the federal government to develop solutions on this issue.

- Need a multi-faceted approach: A wide range of approaches and ideas were discussed, which suggests that a multi-faceted approach is needed to address this issue – rather than implementing a ban in isolation.

Engagement Process and Key Findings by Channel

In-Person Sessions

Public Safety held a series of eight in-person roundtables in four cities: Vancouver (October 22, 2018), Montreal (October 25, 2018), Toronto (October 26, 2018) and Moncton (October 29, 2018). In total, 77 stakeholders participated in these sessions. Stakeholders were invited by Public Safety Canada based on their knowledge, experience, expertise and vested interest in the issue. Stakeholders represented provincial government, law enforcement, municipalities, not-for-profit associations (e.g., health, community services, youth, victims), education, wildlife/conservation, retailers, academia/research, and the firearms/sports shooting community.

The key themes emerging from an analysis of the in-person sessions were:

- Mixed reactions: Some groups were more supportive or mixed in their perspectives on a potential ban/limiting access, while others were strongly opposed

- Enhance frontline enforcement capacity

- Collect and share relevant data

- Focus on crime involving firearms and related crimes

- Focus on underlying factors of gun violence

- Focus on safe storage

- Provide educational opportunities for children and youth

- Work with retailers and the firearms community

- Explore reporting requirements for healthcare system

Written Submissions

Public Safety also called for written submissions from a wide range of stakeholders. Overall, 36 submissions were received from invited stakeholders representing a diversity of sectors and perspectives, including shooting sports, health, government (provincial, territorial and regional), women, municipalities/communities, victims, wildlife/conversation and retailers. Public Safety also received nearly 1,200 submissions from individuals with relevant experience on the issue.

The key themes from the written submissions were:

- Mixed reactions to a potential ban/limiting access

- Collect relevant data on crime involving firearms

- Address risk factors underlying firearms violence

- Focus on illicit firearms trafficking

- Enhance enforcement capacity

- Consult with firearms community/industry

- Provide more mental health supports/screening:

- Provide more education on safe and secure storage

- Address impact of gun violence on women

- Provide clarity in defining/classifying “assault weapon”

Online Questionnaire

In addition to engaging stakeholders, Public Safety developed and launched a questionnaire that was available online to all Canadians. The questionnaire was open for one month, between October 11 and November 10, 2018. During this time, 134,917 questionnaires were completed. In terms of the demographic profile of respondents, more than half were male; most came from either Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia or Alberta; and most lived in an urban setting. Additionally, nearly half owned a firearm.

The key findings from the online questionnaire were:

- Majority of respondents did not support further limiting access to firearms and assault-style firearms

- Focus on the illicit market, not legally-owned firearms

- Target criminals, not lawful owners

- Concerns with “assault weapon” term

- Focus on smuggling and border security

- Stricter screening processes for those acquiring firearms

1. Introduction

With the Government of Canada’s commitment to reduce violent crime involving firearms, Public Safety Canada (“Public Safety”) launched an engagement process in October 2018 to help inform policy, regulations and legislation on this issue. Led by the Minister of Border Security and Organized Crime Reduction, as well as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister (Youth), Public Safety sought to engage and hear from a wide range of stakeholders, which included those both in support of and opposed to limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms. The engagement process included a series of eight in-person roundtables, an online questionnaire, a written submission process, and bilateral meetings with a range of stakeholders.

The engagement process was initiated by a Mandate Letter commitment to “lead an examination of a full ban on handguns and assault weapons in Canada, while not impeding the lawful use of firearms by Canadians”. While the engagement was framed by the examination of a potential ban, the discussion explored several potential measures to reduce violent crime. This included, but was not limited to, restricting access to specific types of firearms.

This report summarizes the key findings across, as well as within each of, the engagement channels. Given the diversity of perspectives on this issue, this report highlights key common themes and ideas shared by participants and stakeholders, as well as unique and divergent views. The goal of this report is to accurately represent “what we heard” on this issue by capturing the voices of all individuals and groups who provided their time, energy and effort to participate in the engagement process. See Annex A for a list of the organizations/groups consulted.

2. Overall Key Findings

This section provides a summary of the key findings from “what we heard” from participants (both public and stakeholders) across all engagement channels.

There were several common themes and ideas shared by participants, even among those who disagreed on the need for a potential ban. These themes include the need to address underlying factors contributing to gun violence, as well as collecting and sharing more relevant data. However, there are some perspectives that are unique to, or were emphasized more strongly by, participants who opposed a ban, such as the need for additional measures to target criminals and not law-abiding gun owners.

In addition to providing views on a potential ban or otherwise limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms, participants shared various strategies to reduce violent crime involving firearms, which are summarized in this section and discussed in detail throughout this report.

There are polarized views on a potential ban and limiting access: Findings from the engagement process suggest participants are strongly polarized on the issue of banning handguns and assault-style firearms. There are many stakeholders on “both sides of the issue” who express strong convictions about a ban. To compare the different engagement channels, the stakeholder views expressed in both the in-person dialogues and written submissions provided a greater variety of perspectives, with representation from both those opposed to and in support of a ban. In contrast, most questionnaire respondents (representing a self-selected group of Canadians) were opposed to a ban.

Target crime and focus on enforcement: Many stakeholders and participants feel strongly that a ban targets law-abiding owners, rather than illicit firearms and crime reduction (particularly gang violence). This is one of the main sensitivities on this issue, and input gathered through this engagement process reflects concern and frustration from the Canadian firearms community. As a result, many participants are calling for a greater focus on the illicit firearms market through enhanced enforcement capacity for law enforcement and border services, as well as harsher punishments for firearms trafficking and gun-related crime. Some felt that a greater focus on enforcement could better resolve the issue of firearm related violent crime than a ban.

Address underlying causes of firearm violence: One point of consensus for many stakeholders and public participants – including both those who oppose and support a ban – is the need to address the socioeconomic conditions that can lead to gun violence. These factors include poverty, a lack of education or employment opportunities, lack of mental health supports and social exclusion. Addressing these issues is especially important for reaching children and youth. It was expressed that more long-term funding and support for community-level programs and initiatives is needed to prevent violent crime.

Collect and share relevant data on gun crime: Many stakeholders were especially interested in improving the collection and sharing of data on gun crime, particularly in terms of sources of illicit firearms (e.g., smuggling, theft, straw purchasing) and the types of crime being committed. Many stakeholders feel that more data needs to be collected on an ongoing basis, and that law enforcement and border agencies need to have mechanisms to share data. Those who oppose a ban or further restrictions are especially concerned, as they suggest that the current data is insufficient to support frontline enforcement efforts and inform policy and legislation.

Willingness for collaboration with the firearms community/industry: Many stakeholders representing various aspects of the firearms community/industry (e.g., retailers, hunters/outdoor enthusiasts, sports shooters) want the opportunity to be more engaged and to collaborate with the federal government on the issue of reducing firearms violence and self-harm.

Need a multi-faceted approach: A wide range of approaches and ideas were provided for reducing violent crime involving firearms, which suggests that a multi-faceted approach – rather than implementing a ban in isolation – is required to effectively address this issue.

3. Key Findings by Engagement Channel

This section provides a detailed summary of the key findings of “what was heard” from the following complementary engagement channels:

- In-person roundtables with stakeholders

- Written submissions

undefinedundefined - Online questionnaire open to the public

- Bilateral meetings with stakeholders

>

3.1 In-Person Roundtables

3.1.1 Overview

To engage a diversity of key stakeholders in the dialogue, Public Safety held a series of eight in-person roundtables in four cities: Vancouver (October 22, 2018), Montreal (October 25, 2018), Toronto (October 26, 2018) and Moncton (October 29, 2018). Two sessions– each 2.5 hours in length – were held per day in each location.

The roundtables focused on gathering stakeholders’ views on: 1) Reducing crime involving handguns and assault-style firearms in Canada, and 2) Limiting illicit access to handguns and/or assault-style firearms. In their discussion, stakeholders were asked to identify challenges and opportunities to help inform measures aimed at reducing firearm-related violent crime in Canada. This included potential measures to limit access, the impact of further restrictions, and strategies to reduce theft, smuggling and straw purchasing. The discussions that followed and the resulting themes emerged naturally in the conversations.

Each roundtable was hosted by either the Minister of Border Security and Organized Crime Reduction or the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister. Senior officials from Public Safety and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) attended as observers. The sessions were supported by an independent facilitator to encourage respectful, open dialogue for all participants, while ensuring a productive discussion. A note-taker attended as well.

In total, 77 stakeholders participated in these sessions, representing a diversity of perspectives on this issue. Stakeholders were invited by Public Safety Canada based on their knowledge, experience, expertise and vested interest in the issue with invitations sent primarily to organizations rather than individuals. Stakeholders represented provincial government, law enforcement, municipalities, not-for-profit associations (e.g., health, community services, youth, victims), education, wildlife/conservation, retailers, academia/research, and the firearms/sports shooting community.

3.1.2 Key Findings

Mixed reactions to a potential ban/limiting access: Overall, participants were divided in their views on a ban. Some groups were more supportive or mixed in their perspective, while others were strongly opposed.

Those in support of a ban or further restrictions recognized that while firearms could still be available illegally if a ban were implemented, further restrictions could reduce the number diverted to illicit purposes. Some noted legal firearms are used in violent crime (e.g., in rural areas, domestic violence). The strongest supporters of a ban suggested handguns and assault style weapons should not be available to anyone except law enforcement and military.

In contrast, participants opposed to a ban emphasized it would be ineffective because it affects law-abiding owners, and not the illicit market or criminal use. They stated there needs to be greater focus on enforcing existing regulations and more broadly, differentiating between illicit and legal firearms use.

“The only way to [reduce gun violence] is if the government puts the money and resources into the police to go out and do their jobs.”

Enhance frontline enforcement capacity: A main theme across most sessions (including participants both opposed to and in support of a ban) was the need to enhance frontline enforcement capacity to tackle the sources of illicit firearms. Overall, participants were most concerned about smuggling and border security given Canada’s proximity to the U.S., and less about theft and straw purchasing (not viewed as a significant issue by some participants).

Enhancing enforcement capacity requires increased funding/resources and tools for the frontline, particularly law enforcement agencies at all levels and for the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). Participants emphasized the need for enhanced inspection and investigatory capacity at the municipal level, especially when dealing with gangs and organized crime. Additionally, participants identified the need for capacity to conduct regular and impromptu inspections (e.g., to ensure compliance with storage requirements), ensure prompt seizure of firearms in dangerous situations (e.g. mental health crisis, domestic violence), and conduct diligent follow-up with firearms owners. Many suggested improving frontline resources would better enforce existing firearms regulations.

Additionally, some felt the Canadian Firearms Program (RCMP) and the provincial and territorial Chief Firearms Officers (CFOs) could have a role in screening individuals and identifying trends, such as unusual or suspicious purchasing patterns. This could involve working more closely with key partners like retailers.

Collect and share relevant data: Several stakeholders across all sessions called for improvements in data collected related to gun violence in Canada, and how it is shared between relevant agencies and organizations. Many felt this data is currently not available, incomplete or of poor quality. Participants stated better data collection and sharing is critical for supporting frontline enforcement efforts and to inform public policy on firearms

“We need a more solid intelligence picture.”

Specifically, many felt data collection needs to be enhanced. This could involve collecting more data on gun violence, illicit firearms sourcing (e.g., domestic vs. international, smuggling vs. theft vs. straw purchasing) and how much firearms crime is committed by licenced vs. non-licenced individuals. Additionally, participants emphasized the value of having more data related to root causes of gun violence, informing further research and strategic decisions to target specific communities and make effective socioeconomic investments.

Many participants discussed the need to involve more organizations and sectors in data collection, analysis, and sharing, as multiple sources are needed to build comprehensive intelligence on gun crime. In addition to law enforcement and border services, participants flagged the need for better information flow between government, healthcare providers, and community-based partners. This would be especially valuable for providing police and border services with greater “on the spot” access to relevant data.

Focus on crime involving firearms and related crimes: Similar to the previous theme on enforcement capacity, many stakeholders (particularly those more likely to oppose a ban) called for a greater focus on crime involving firearms and associated criminal activity, particularly gangs/organized crime (e.g., controlling drug markets is a significant driver of illicit firearms). Due to higher numbers of incidents, some participants felt efforts should focus on crime occurring in large cities, such as Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. However, a few participants clarified that firearms violence is not just about gangs – it includes domestic violence and suicide.

“Gangs will continue to get guns. It’s a requirement of their business… That’s why we go back to the demand side.”

In addition to specialized enforcement measures (e.g., police teams with enhanced inspection powers dedicated to gangs and illicit firearms), many participants focused on establishing harsher penalties (with fewer reduced sentences) for firearms-related crimes. Many suggested there is currently too much leniency and not enough deterrence, resulting in high levels of re-offending. For example, some participants suggested mandatory minimum sentencing (others strongly opposed this measure) and, generally, punishing criminals to the “full extent of the law.”

“If there is fear of losing your freedom for a significant amount of time, not just four months… maybe I won’t use a gun.”

Some participants also suggested the need for proactive measures, particularly preventing children and youth from joining gangs or committing crimes. These ideas are discussed in greater length later under the theme “Provide educational opportunities for children and youth”.

“We need to worry less about border crossings and more… Why is this person not thinking about accessing job opportunities instead [of committing a crime or joining a gang]?”

Focus on underlying factors of gun violence: Several stakeholders emphasized the importance of addressing socioeconomic factors that can be root causes of gun violence, such as poverty, a lack of education and employment, homelessness, social exclusion/isolation and mental health issues.

To address these systemic issues, many participants identified the need for long-term community-level investments providing upstream supports and services and, more broadly, improving socioeconomic conditions. It was noted this is important because municipalities often lack funding and resources needed to sustain programs and initiatives over the long term. Additionally, some emphasized the need to mobilize community members to be actively involved and to ensure initiatives are culturally appropriate. This type of approach helps individuals and families build resilience and prevent their involvement in criminal activities resulting in gun violence.

“People need to feel socially included, have income and feel like they live in a safe environment.”

“If it feels safer on the street [children and youth] may join a gang because it feels like family.”

Some participants suggested certain risk factors could be used to inform the screening of individuals trying to acquire firearms, such as mental health issues, a history of violence, or exposure to domestic violence.). It was noted this could be especially helpful in identifying at-risk/vulnerable youth.

However, some participants with experience in the mental health sector also cautioned against stigmatizing individuals with mental illness, as they are not more at risk of being violent, particularly if they are undergoing treatment. They explained the link between mental health and gun violence is often overstated, ignoring the broad range of factors involved.

“Be careful of stigma… Most people with mental health issues are not dangerous.”

Focus on safe storage: Across almost all sessions, many stakeholders discussed the need to prioritize safe storage of firearms. However, participants’ perspectives on what is needed differed, largely depending on their views on a potential ban/limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms. For example, those in support of a ban and/or restrictions called for stricter storage regulations for all types of firearms, both for private owners and retailers, to help prevent youth, individuals in mental health crisis, and individuals under the influence of drugs or alcohol from accessing firearms.

Participants in multiple sessions suggested considering non-residential storage options, such as requiring gun owners to leave their firearms at a gun club/shooting range or centralized storage facility, especially in large urban cities. One stakeholder described the success of this type of initiative in the context of their experience working in a First Nations community, in which community members agreed to voluntary storage in a community gun locker following a period of rampant gun violence. Another idea was to introduce inspection of private storage, which could include regular and impromptu inspections to ensure the firearm is being stored securely and is still in the individual’s possession.

In contrast, stakeholders that were opposed to limiting access were also against the idea of centralized, non-residential storage, suggesting that it presents a bigger target for firearms theft. Rather, some identified the need for more education on safe storage (e.g. a national campaign), recognizing that some owners may not be complying with current storage requirements. Additionally, some were open to exploring how requirements could be strengthened, such as requiring both firearms and ammunition to be stored separately and securely. Members of the firearms community emphasized further requirements need to be fair and developed in collaboration with gun owners, as they explained that most already comply with the existing regulations.

Provide education opportunities for children and youth: Some stakeholders, particularly those more concerned with the presence of firearms in communities, feel engaging children and youth should be a priority for preventing violence involving firearms. Efforts to reach all ages are important; many stakeholders who work directly with children and youth discussed the often “clear trajectory” for at-risk individuals who are more likely to join gangs or go to jail. These stakeholders emphasized the importance of early engagement through school-based programs to educate young children (e.g., teaching non-violent action/expression), and targeted initiatives for older at-risk youth. Supporting these efforts requires sustained funding. Additionally, some partner-based initiatives were highlighted, such as the partnership between the Calgary Police Service and the YouthLink Calgary Police Interpretive Centre, which provides educational opportunities on law enforcement careers.

“With respect to children in gangs… High school is too late. We’re looking at grades 7 and 8. After that it’s beyond our control. I’ve listened to telephone calls of high-ranking gang members talking to young kids.”

Many stakeholders highlighted the need to identify and support at-risk youth, especially those who may be in the child welfare system, have experienced trauma, are not attending school regularly, and are exiting gangs or juvenile detention. Efforts to reach these youth should involve both schools and law enforcement as partners in outreach and delivery, as well as “in the know” community members and groups. More broadly, some stakeholders voiced concerns with how children and youth are increasingly desensitized to gang and gun culture because of the news, popular media and video games. As a result, participants noted a public awareness campaign may be helpful, similar to recent ones about driving and texting or driving while under the influence of cannabis.

Additionally, a few firearms community members discussed efforts they have taken, such as teaching responsible firearms ownership through youth sports shooting programs. Some discussed the need to broaden these types of initiatives into schools to reach higher numbers of children and youth.

Work with retailers and the firearms community: Several stakeholders representing the firearms community/industry identified the need for greater engagement and collaboration. Many participants feel that firearms owners need to be seen in a more positive light and treated like allies providing valuable expertise and capacity. These stakeholders noted many community members are already contributing to solutions and demonstrating best practices, such as gun clubs providing free firearms safety training, and retailers identifying suspicious behaviour and purchases.

“Work with us and not against us.” “These are technical problems that need technical solutions.”

Some ideas to work with the firearms community included creating a working group to share knowledge and ideas, providing more education/training and resources to youth and the broader public on firearms safety, and collaboratively developing codes of practice for firearms owners (e.g., maintaining a personal inventory of firearms owned, including information on make, model, and serial number which could be shared with police in the case of theft). A few stakeholders also discussed the need for collaboration between CFOs and retailers for more active surveillance of straw purchasing, while some identified a greater role for the Canadian Firearms Program in identifying trends.

Explore reporting requirements for healthcare system: One theme discussed by some participants in various sessions is whether healthcare professionals should be responsible for reporting issues that may be related to firearms violence. Citing the example of Bill 9 in Quebec, some suggested that physicians could be permitted to notify authorities (e.g., law enforcement, CFOs) of suspicious or concerning behaviour that may justify the seizure of firearms. For example, reporting may be required when treating an individual for serious mental health issues. More generally, a few participants discussed the need to monitor trends in firearms injuries, or to introduce mandatory reporting of gunshot wounds to police.

Additional findings mentioned by some (but fewer) participants in the in-person roundtables include:

- Concerns with lack of clarity on “assault weapons”: Stakeholders opposed to a ban voiced concern with the term “assault weapon,” which they feel is misleading because characteristics which were interpreted as defining this term (e.g. high-capacity, fully-automatic) are prohibited in Canada. They suggested a more accurate term is needed. They also noted the use of this language is disrespectful to the firearms community because it propagates fear. The term “assault-style firearms” has since been adopted.

- Explore the gendered impacts of violence: Some stakeholders discussed how more attention needs to be paid to ways that gun violence impacts people of different genders. For instance, firearms violence is predominately committed by men, and it is mostly men who are victims of firearms violence. Several participants also noted the impacts of gun violence on women. Examples were raised, including incidents or threats of intimate partner violence (the victims of which may be affected by the presence of legal firearms), and young women joining gangs or being used by them (e.g. straw purchasing). It was also noted that emergency room nurses, who are overwhelmingly female, are firsthand witnesses of the impacts of gun violence. Participants suggested efforts should be made to work more with police (e.g., enhancing capacity for seizure in domestic violence cases) and community partners, and proposed an education campaign for at-risk women and girls.

- Consider various licencing restrictions: While many participants did not provide specific suggestions for changes to the licencing regime (beyond their views on whether or not to limit access), some of the ideas suggested include: more stringent background checks (e.g., to identify mental health issues, interaction with police), conducting frequent safety audits of owners, and requiring more justification for purchases. Additionally, a few participants identified the need for increased due diligence and seizure for expired registrations, which could involve community members working with law enforcement to address capacity issues.

- Consider banning imitation firearms: A few participants, particularly those in large cities, expressed concern with the increasing popularity of imitation firearms, such as airguns and BB guns. For example, some explained how they contribute to gang culture, take up law enforcement resources (for instance, police racing to the scene to respond) and can cause harm due to the high-velocity of some models. As a result, some suggested that imitation firearms be banned.

3.1.3 Data Collection and Analysis

Detailed notes were taken by an independent note-taker to capture the discussion at all eight sessions. These notes were used to write a roundtable summary report for each session, which synthesized the key themes and ideas from stakeholders in response to the discussion questions.

To develop this overall summary report, all roundtable summary reports were reviewed thoroughly to identify the overarching themes from stakeholders across all sessions. More specifically, the focus was on highlighting: 1) Views on a potential ban/limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms, and 2) Priorities and ideas for reducing violent crime. The detailed session notes were also reviewed to ensure that key details and quotes were also captured in this report.

3.2 Written Submissions

3.2.1 Overview

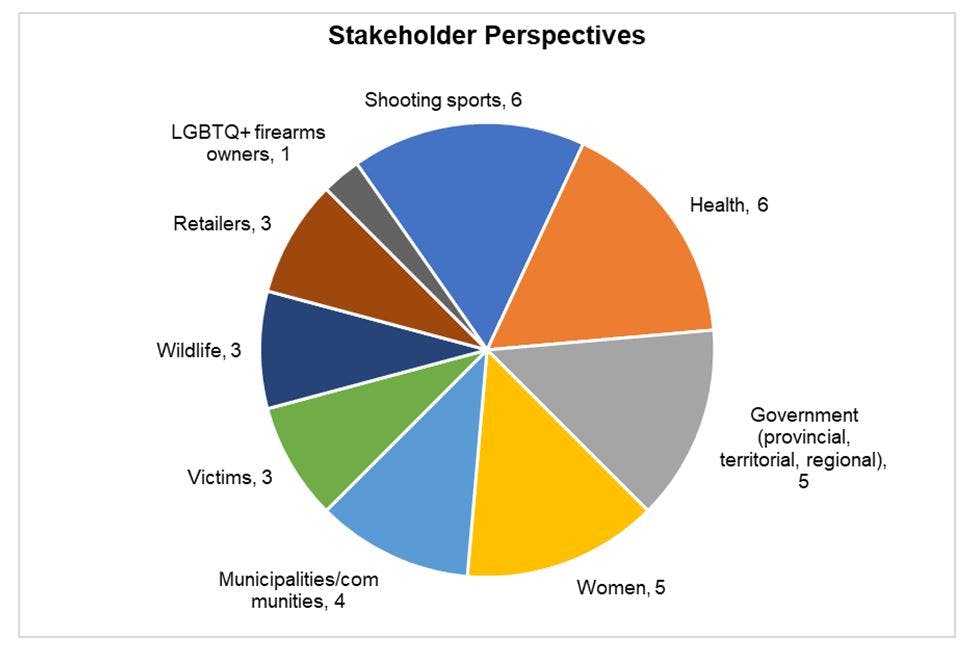

In addition to the online questionnaire and in-person roundtables, Public Safety called for written submissions from a wide range of stakeholders. Submissions came in a variety of formats, including position/research papers, briefing notes/memos and emails. Overall, 36 submissions were received from invited stakeholders representing a diversity of groups/organizations, sectors and perspectives which are identified in the chart below:

Image Description:

Types of Stakeholders

There were a total of 36 stakeholders who submitted a written submission to Public Safety Canada. The graph provides a breakdown of the different types of stakeholders. Six stakeholders represented shooting sports, six represented health professionals, five were governments (provincial, territorial, and regional), five were women’s-focused organizations, four were municipalities and communities, three were victim-focused organizations or victims’ advocates, three were wildlife organizations, three were retailers, and one represented LGBTQ+ firearms owners.

3.2.2 Key Findings

Opposition to a ban

Many stakeholders explicitly opposed a potential ban and/or further limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms. This included all the shooting sports clubs/associations and retailers, most of the academic/researchers and wildlife/conservations associations, as well as a territorial government, an association representing rural municipalities and a group representing LGBTQ+ firearms owners.

The top rationales cited by these stakeholders for their position on a ban and further restrictions include:

- A ban would impact lawful owners rather than criminals: The most cited reason for opposing a ban is, according to several stakeholders, it does not effectively target the illicit firearms market or reduce crime; rather, it impedes and punishes lawful owners who use firearms for a variety of legitimate purposes, such as sports and target shooting. This view was particularly strong among shooting sports clubs/associations, retailers and wildlife/conservation associations. Instead, some suggested greater focus on addressing gang violence, especially in large cities like Toronto.

“You are reacting to a crime wave, no question, but not a firearms problem.”

- Focus on underlying causes of gun violence: Several stakeholders discussed how a ban would not address the underlying causes of gun violence, which include broad social, economic and cultural factors. For example, some suggested that reducing gun violence (and associated criminal activity, like gang involvement) is about addressing poverty, lack of employment opportunities and mental health issues.

- Negative economic impact on industry/sport: Some of the shooting sports clubs/associations, retailers and wildlife/conservation associations advised a ban would have a significant negative impact on both the sporting goods and shooting sports industry. Specifically, some explained that a ban would hurt small businesses and could result in the closing of gun ranges and job losses in communities.

“Any action the Government takes that will adversely impact these small businesses must take into account the economic consequences of those actions.”

- Not enough data/evidence to support a ban: Some stakeholders also felt there is insufficient data to support a ban on handguns or assault-style firearms, particularly on the sources of firearms used in crimes (e.g., straw purchasing) and the individuals who are committing these crimes.

Supportive of a ban

Several stakeholders explicitly supported a potential ban and/or further limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms. This included some of the health associations/groups, victims-focused organizations, women-focused organizations, one provincial Ministry, one governmental organization and one of the municipally-focused organizations.

These stakeholders cited the following rationales for supporting a ban and further restrictions:

- Reduces harm/lethality: Several stakeholders, particularly those representing women- and victim-focused organizations, support a ban because, in their view, firearms are dangerous and increase the risk of harm and lethality in communities. As a result, while many acknowledged the problem of illicit firearms and crime, they explained legal firearms are also a concern for many stakeholders. For example, they noted the presence of legal firearms in a household is a significant risk factor in situations of domestic violence or suicide.

“Simply put, access to firearms increases the lethality of violent encounters.”

- Contributes to addressing violent crime/gang violence: Some stakeholders feel a ban, in combination with other measures, will help reduce violent crime in communities, such as gang violence. While they recognized a ban would not address concerns with illicit firearms acquired through smuggling and trafficking, it could still have an effect in reducing or impeding domestically sourced legal firearms stolen or diverted for illicit or criminal use.

“We support measures to reduce or eliminate the availability of legal handguns.”

- No legitimate use/purpose: A few stakeholders support a ban because they do not believe there are any legitimate uses for handguns and/or assault-style firearms for civilians, even for hunting. While some acknowledged there may be some sport/recreational benefit for individuals, they do not think providing legal access to these firearms is justified with the safety risk they pose.

“As these firearms have no legitimate use in hunting, current owners may only legally use them for target shooting or collecting. This is not a compelling enough reason to justify the risk they pose to public safety.”

Key suggestions to reduce violent crime

While not all stakeholders expressed a clear position on a ban, there were a number of areas of common ground, resulting in shared suggestions to reduce violent crime involving firearms.

The common themes expressed the most are:

- Collect relevant data on crime involving firearms: One of the top themes expressed by a diversity of stakeholders (both in support of and opposed to a ban) reflects concerns there is not enough data/evidence available to inform firearms legislation. Stakeholders suggested addressing gaps in data on gun crime, particularly the source of guns being used in crimes (e.g., legal vs. illicit; theft vs. smuggling vs. straw purchasing). Other data points of interest include what types of guns are being used, who is using guns to commit crimes (e.g., gang-related), and where crimes are occurring (e.g., urban centres vs rural vs Northern).

This requires the consistent, ongoing collection of relevant and credible data across jurisdictions, as some questioned the criminal intelligence that is currently available. For example, a few participants wondered whether straw purchasing should be a concern, citing a lack of data available. Additionally, one stakeholder felt that reported increases in domestically-sourced vs. smuggled firearms is inaccurate and “speculative.”

“A national response demands that all those concerned operate from a common set of facts.”

“We do not recommend making changes to legislation until the data is further available and a course of action that would lead to drops in gun violence is recommended, that takes into account the evidence and proven practice.”

- Address risk factors underlying firearms violence: Another top theme among stakeholders (both in support of and opposed to a ban) is to address the risk factors that can be determinants leading to crime and gun violence over time. More specifically, several stakeholders emphasized the long-term impact of socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, a lack of employment opportunities, inadequate housing, and social exclusion. In their view, there needs to be greater focus on providing the services needed to build more supportive environments and improve socioeconomic conditions. This will help empower individuals and families, particularly in vulnerable communities and major urban centres. Many noted this will require sustained funding for community-based programs/initiatives (e.g., crime/gang prevention, life skills, cultural development) and infrastructure (e.g., libraries, recreational and health facilities).

Similarly, some stakeholders identified the need for an interdisciplinary “public health” approach to gun violence, which focuses on root causes and prevention, not just enforcement through policing and the criminal justice system. For example, some called for more mental health supports, not only for those affected by gun violence but as a means of primary prevention.

“Focusing too narrowly [on one issue] is concerning if policy and legislation are not accompanied by efforts to address broader socio-economic and health care inequities and to invest in relevant infrastructure.”

- Focus on illicit firearms trafficking: Many stakeholders, particularly those opposed to a ban, emphasized the need to focus on curbing the illicit firearms market. Some stakeholders called for stricter penalties to serve as a deterrent for firearms trafficking through smuggling, theft and straw purchasing (although some felt that this is not a large-scale problem), as well as other illegal acts, such as removing serial numbers from firearms. A few stakeholders noted concerns with plea bargaining and reduced sentencing, which they felt was too common in these types of cases.

In terms of addressing specific sources of illicit firearms, some called for more funding for CBSA to address smuggling. Additionally, some retailers expressed willingness for greater collaboration on tracking and reporting suspicious activities, such as large purchases of firearms and ammunition indicating potential straw purchasing. A few stakeholders also identified the need for a mechanism to be able to monitor and flag large and unusual purchases. For example, one government submission suggested that current indicators used to help notify police of suspicious purchases may need to be revisited to reduce the quantity and timeframe, which could help combat straw purchasing. Additionally, this stakeholder also suggested reviewing the regime for reporting lost or stolen firearms, as it’s currently very difficult to prosecute.

“Punishment for firearm crimes must be severe so as to act as a deterrent. Individuals who are apprehended with illegal or illicit firearms must be punished.”

“Criminal violence is driven by a small number of repeat offenders, not by the millions of Canadians who legally own firearms… firearms legislation focused on general ownership fails to reduce rates of criminal violence.”

- Enhance enforcement capacity: Related to the previous theme, several stakeholders, particularly those representing shooting sports associations, wildlife/conservation associations and former law enforcement officers, suggested enhancing enforcement capacity to tackle crime involving firearms and crime-related activities, such as gangs, drugs and terrorism. For some, there is a need for more “aggressive” action in these areas, particularly to ensure existing firearms legislation is enforced, rather than justify the need for further restrictions like a ban.

This requires more funding for law enforcement (federal, provincial and municipal agencies), CBSA and intelligence agencies to ensure they have adequate frontline staff, resources and tools for detection, investigation and prosecution. The development of effective strategies targeted at crime was also noted, as well as a data strategy. Individuals with law enforcement experience also discussed the importance of specialized intelligence-gathering and routine checking capacity for police in big cities (e.g., similar to the previous Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy). Additionally, one government stakeholder clarified that gangs are expanding beyond major urban centres into smaller communities, as well as across borders. - Consult with firearms community/industry: Several stakeholders representing those opposed to a ban suggested that the federal government seek meaningful engagement with the firearms community and industry. This includes greater collaboration with provincial and territorial partners, communities most affected by crime involving firearms, rural communities, Indigenous communities and industry groups (e.g., Canadian Sporting Arms and Ammunition Association).

Leveraging their experience could help decision-makers better understand the issues involved and potential impacts of legislative changes (e.g., protection of livestock for rural landowners, financial impact on small businesses), thereby informing solutions to reduce violent crime involving firearms while not impeding the lawful use of firearms by Canadians. For example, this could include promoting best practices for firearms owners (e.g., keeping personal firearms inventory in a safe place to assist police in case of theft) and retailers (e.g., reporting suspicious activity). Stakeholders felt this type of dialogue would help contribute to a more informed, evidence-based approach, while also promoting engagement with and compliance by the firearms community: “Provide clear messaging that firearms owners are themselves a critical component in the fight against gun crime”.

“This working cooperation already exists in some sectors. Law enforcement agencies work with the auto insurance agencies to enhance road safety, why not with firearms?

- Provide more mental health supports/screening: Some stakeholders emphasized the importance of providing mental health prevention, intervention and treatment supports for individuals, which could reduce violent crime involving firearms. Some felt this requires more adequate funding to support community-level services and reduce barriers to access these services. Additionally, a few stakeholders suggested screening individuals for mental health issues if they are looking to acquire and possess firearms. For example, one shooting sports club called for enhanced mental health background checks (e.g., providing a health report from a doctor) when individuals apply for a PAL, as they suggested there are often mental health concerns when violence involving firearms is committed.

However, while mental health-focused organizations agreed with the need for more supports, they expressed strong concern with the misperception that gun violence and mental illness are closely correlated, as this is often exaggerated in media reporting and in the broader public discourse. They explained individuals suffering from mental illness are often discriminated against and criminalized, and that more important determinants of violence include having a history of violence and non-supportive environments –not whether someone has mental health issues.

“In considering the impact of mental illness on gun violence… in most cases, the most significant predictor of violence is not the presence of mental illness but rather a history of violence.” - Provide more education on safe and secure storage: Stakeholders representing retailers, shooting sports associations and one women-focused organization called for more rigorous public education on safe, responsible storage for owners, which could be provided upon purchase of firearms. This could help deter theft while enhancing public safety. Additionally, one victims-focused organization suggested the federal government examine after-hours commercial storage regulations.

- Address impact of gun violence on women: Stakeholders representing women- and victims-focused organizations discussed the importance of acknowledging how women and girls are disproportionately impacted by violence involving firearms, such as through domestic violence, and human trafficking. They suggested a variety of measures to address domestic violence specifically, including enhancing police protocols/capacity in intervention (e.g., seizure of firearms), stricter background checks (e.g., alerting partners/ex-spouses of PALs), and raising awareness of violence against women. More broadly, some suggested further analyzing trends in gender-based violence (e.g., relationship between firearms and cycle of violence against women) and gender norms related to violence (e.g., gang violence and mass shootings perpetrated by males) to inform future legislation.

- Provide clarity in defining/classifying “assault weapon”: Some stakeholders representing retailers and wildlife/conservation associations expressed strong concern with the lack of a clear definition of “assault weapon”. In their perspective, the term has led to misrepresentation in the media and broader public misunderstanding that implies both harm and availability of fully automatic firearms. Additionally, some stakeholders noted concerns that certain weapons (e.g., “black guns”) are assumed to be more dangerous based solely on their appearance. One stakeholder suggested adopting more appropriate language and creating a separate sub-group under restricted firearms, such as “modern sporting rifle or “military-style carbine.”

Additional themes (shared by fewer stakeholders) include: - Implement a buyback program: A few participants (representing victims-focused organizations and research/academia) suggested a buyback program to get more handguns and other firearms “off the street.” One stakeholder explained both the street and market value would need to be considered to create incentives for people to voluntarily hand over their guns. This could also be coupled with amnesty from prosecution and anonymous “handovers”, as well as various legislative reforms around licencing, registration, sales (e.g., restoring the requirement for firearms dealers to record sales and retain records of unrestricted firearms) and transportation (e.g., eliminating automatic authorizations to transport for prohibited and restricted firearms).

Revise firearms classification:

- Three stakeholders (representing government, victims and research/academia) provided clear suggestions for revising firearms classification, which included:

- “Automatically, but temporarily” classify all new firearms as prohibited until properly classified

undefinedundefinedundefined - Ensure adequate resources for the Canadian Firearms Program: Additionally, two stakeholders (representing municipalities and shooting sports) identified the need to ensure that the Canadian Firearms Program has enough resources to carry out some important responsibilities effectively and in a timely manner, specifically background checks and issuing permits and Authorization to Transport (ATT).

3.2.3 Data Collection and Analysis

The data from the stakeholder submissions was received in a variety of formats, including Word and PDF documents and emails. Similar to the approach used for the in-person roundtables, the analysis focused on understanding stakeholders’:

1) Views on ban/limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms, and 2) Priorities for reducing violent crime. Each submission was reviewed thoroughly, with key points/messages and relevant data/evidence extracted into an analysis framework. Once all submissions were reviewed, the analysis aimed to identify both overarching and divergent themes across stakeholders.

3.2.4 Unsolicited Submissions

Overview

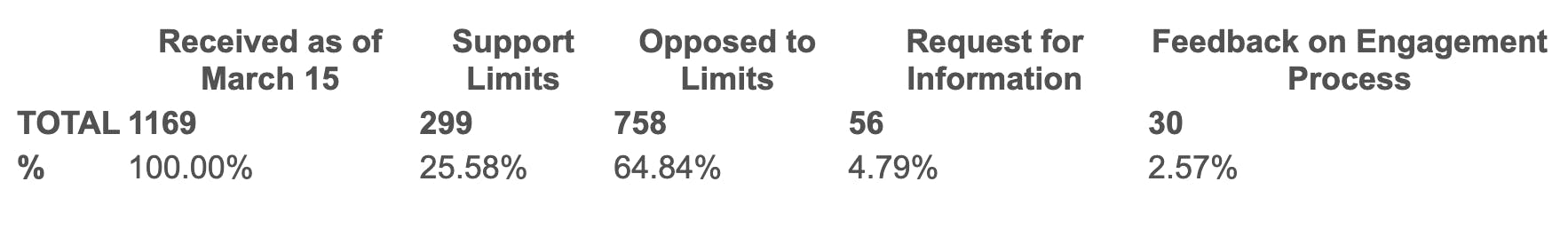

Public Safety also received nearly 1,200 submissions via email, mail and fax from individuals with relevant experience on the issue, including firearm ownership, federal/provincial law enforcement, border security, emergency medicine and farming/ranching.

Image Description:

Canadians were invited to share their perspectives through mail, email and fax. A total of 1,143 letters were received in direct response to the engagement on Reducing Violent Crime. Of these: 758 did not support a limit, 299 did support a limit, 56 requested additional information, and 30 provided feedback on the engagement process.

Key Findings

Supportive of a ban:

- Strong support for a ban on firearms in major urban centers.

- Increase efforts at the point of sale to prevent firearms from becoming illicit.

- In areas affected by gun violence, provide funding for mental health supports, social and economic programs, affordable housing, jobs, and social and health services.

Opposed to a ban:

- Bans on handguns and/or assault weapons would only impact law-abiding gun owners in Canada.

- Efforts should focus on criminal justice, crime prevention, border security and/or mental health policies.

- Existing gun laws and policies in Canada are already robust and effective.

Feedback on Engagement Process:

- Online Questionnaire: The following concerns were expressed about the questionnaire:

undefinedundefinedundefinedundefined - In-person engagement sessions: Concerns that the in-person engagement sessions were by invitation only, and that a list of invitees had not been made public.

- Terminology: Concerns that the definition of ‘assault weapons’ is not consistent or well defined.

- Crime and gun violence statistics presented to date are insufficient or do not support the need to apply further restrictions on legal gun ownership.

Request for Information:

- Requests to receive an invitation to the in-person engagement sessions

- Enquiries about who was invited to the in-person engagement sessions

Data Collection and Analysis

Emails and letters were categorized by one main theme, with priority given to whether they were supportive of or opposed to a potential ban. Many of the emails and letters also had a secondary theme; in particular, many respondents which were opposed to additional limitations also included feedback on the engagement process or a request for information.

Of the responses received, 1103 were sent via email, 58 were sent via mail, and 8 were sent via fax. Public correspondence sent to Minister Blair and Minister Goodale has not been included in this analysis.

3.3 Online Questionnaire

3.3.1 Overview

To engage this general public in the dialogue, Public Safety developed and launched a questionnaire that was available online to all Canadians.

The questionnaire contained a series of quantitative and qualitative questions aimed at gathering citizens’ views on potential limiting of access to handguns and assault-style firearms, focusing efforts on illicit or legally-owned firearms, and various aspects of the illicit market, including smuggling, theft and straw purchasing. Throughout the questionnaire, respondents had the opportunity to provide their own perspectives and ideas on what they thought would be most effective. Additionally, respondents answered various profile and demographic questions.

The questionnaire was open for one month, between October 11 and November 10, 2018. During this time, 134,917 questionnaires were completed. Footnote1

Respondent Profile Highlights

The following demographic information was collected from respondents, providing a picture of who completed the questionnaire:

- Gender: More than half of the respondents identify as male (61%) and almost one-third (30%) are female. One percent identified as “Other” and 8% selected “Prefer not to say.”

- Age: Respondents represent a diversity of ages between 18 and 74 years old (2% were over 75 and none were under 18), with most (70%) under the age of 55.

- Region: Most respondents (85%) come from four provinces: Ontario (34%), Quebec (21%), British Columbia (16%) and Alberta (14%). Other provinces were far less represented, and no respondents indicated coming from Prince Edward Island or the territories.

- Type of residence: More than two-thirds of respondents (70%) live in an urban setting, and almost one-quarter (23%) live in rural areas.

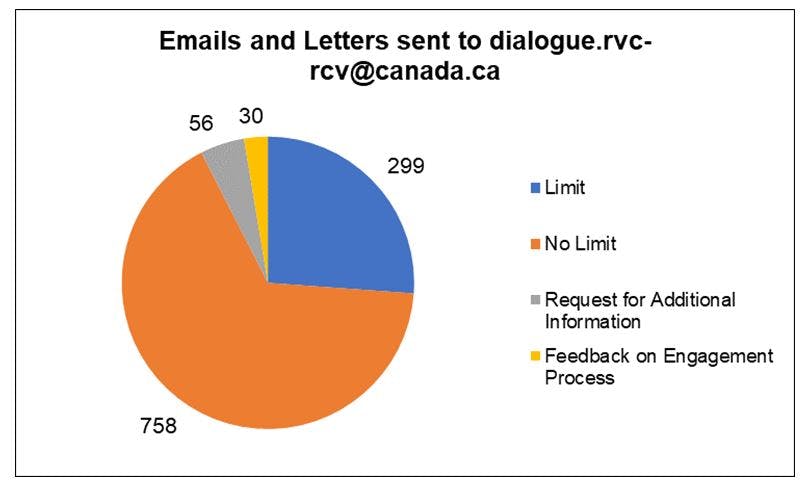

Respondents were also asked about firearm and handgun ownership:

Image Description:

Do you currently own a handgun/firearm The questionnaire asked respondents if they currently own a firearm or a handgun. Of the 132,218 respondents who answered the question on whether they own a firearm, 47% said “Yes”, 40% said “No”, and 13% indicated they “Prefer not to say”. Of the 132,214 respondents who answered the question on whether they own a handgun, 30% said “Yes”, 57% said “No”, and 13% indicated they “Prefer not to say”.

3.3.2 Key Findings

This section summarizes the key findings from the online questionnaire, which reflect the series of quantitative and qualitative questions respondents answered.

Views on limiting access to handguns and assault-style firearms

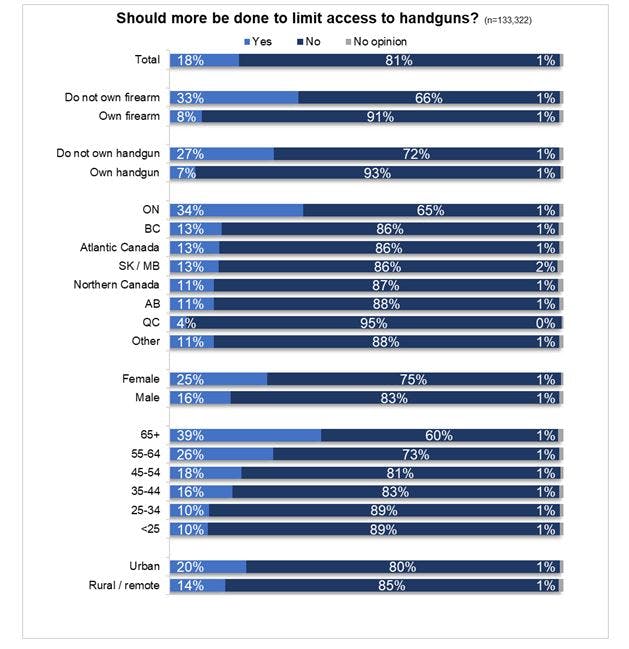

Most respondents (81%) did not want more to be done to limit access to handguns. The following chart displays how respondents answered across various demographics and the profile question on firearms/handgun ownership.

Image Description:

Analysis of opinions on whether more should be done to limit access to handguns and other demographic information.

The questionnaire asked respondents if they believe more should be done to limit access to handguns. 133,322 respondents answered this question.

Overall, when asked if they believe more should be done to limit access to handguns, 18% said “Yes”, 81% said “No”, and 1% indicated they had no opinion.

A cross tabulation analyzed the relationship between their answer to this question and other variables, specifically their gun ownership status and demographic information. Due to rounding, percentages do not always sum to 100%.

Firearm owners were more likely to state that no further action should be taken to limit access to handguns. 8% of firearm owners indicated more should be done, 91% indicated no more should be done, while 1% had no opinion. 7% of handgun owners indicated more should be done, 93% indicated no more should be done, while 1% had no opinion. For those who do not own a firearm, 33% indicated more should be done, 66% indicated no more should be done, and 1% had no opinion. For those who do not own a handgun, 27% indicated more should be done, 72% indicated no more should be done, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows regional variations. For Ontario residents, 34% were supportive of further action, 65% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For residents of BC and Atlantic Canada, 13% were supportive of further action, 86% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For residents of Saskatchewan/Manitoba, 13% were supportive of further action, 86% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For residents in Alberta, 11% were supportive of further action, 88% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For residents in Northern Canada, 11% were supportive of further action, 87% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For Quebec residents, 4% were supportive of further action and 96% were not supportive. For those who indicated “Other”, 11% were supportive of further action, 88% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows variations by gender where women were more supportive than men of further action. For women, 25% were supportive of further action, 75% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For men, 16% were supportive of further action, 83% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows variations by age group, suggesting a relationship between someone’s age and their support for further action on handguns, where older people are more supportive of action. For people aged 65 or older, 39% were supportive of further action, 60% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For people aged 55-64, 26% were supportive of further action, 73% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For people aged 45-54, 18% were supportive of further action, 81% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For people aged 35-44, 16% were supportive of further action, 83% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For both people aged 25-34 and people younger than 25 years old, 10% were supportive of further action, 89% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows variations by area of residence, with urban residents more supportive of action. For people living in an urban area, 20% were supportive of further action, 80% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For people living in a rural or remote area, 14% were supportive of further action, 85% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion.

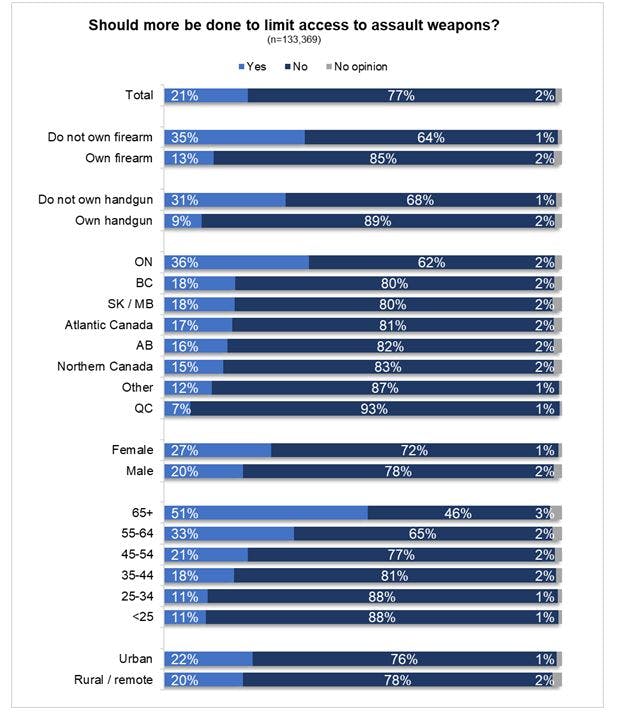

Similarly, most respondents (77%) did not want more to be done to limit access to assault-style firearms.

Image Description:

Analysis of opinions on whether more should be done to limit access to assault-style firearms and other demographic information.The questionnaire asked respondents if they believe more should be done to limit access to assault weapons. 133,369 respondents answered this question.

Overall, when asked if their believe more should be done to limit access to assault weapons, 21% said “Yes”, 77% said “No”, and 2% indicated they had no opinion.

A cross tabulation was completed to analyze the relationship between their answer to this question and other variables, specifically their gun ownership status and demographic information. Due to rounding, percentages do not always sum to 100%.

Firearm owners were more likely to state that no further action should be taken to limit access to handguns. 13% of firearm owners indicated more should be done, 85% who indicated no more should be done, while 2% had no opinion. 9% of handgun owners indicated more should be done, 89% indicated no more should be done, and 2% had no opinion. For those who do not own a firearm, 35% indicated more should be done, 64% indicated no more should be done, and 1% had no opinion. For those who do not own a handgun, 31% indicated more should be done, 68% indicated no more should be done, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows regional variations. For Ontario residents, 36% were supportive of further action, 62% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For BC and Saskatchewan/Manitoba residents, 18% were supportive of further action, 80% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For Atlantic Canada residents, 17% were supportive of further action, 81% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For Alberta residents, 16% were supportive of further action, 82% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For residents in Northern Canada, 15% were supportive of further action, 83% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For Quebec residents, 7% were supportive of further action, 93% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For those who indicated “Other”, 12% were supportive of further action, 87% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows variations by gender where women were more supportive than men of further action. For women, 27% were supportive of further action, 72% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For men, 20% were supportive of further action, 78% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows variations by age group, suggesting a relationship between someone’s age and their support for further action on assault-style firearms, where older people are more supportive of action. For people aged 65 or older, 51% were supportive of further action, 46% were not supportive, and 3% had no opinion. For people aged 55-64, 33% were supportive of further action, 65% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For people aged 45-54, 21% were supportive of further action, 77% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion. For people aged 35-44, 18% were supportive of further action, 81% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For both people aged 25-34 and people younger than 25 years old, 11% were supportive of further action, 88% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion.

The cross tabulation shows variations by area of residence, with urban residents more supportive of action. For people living in an urban area, 22% were supportive of further action, 76% were not supportive, and 1% had no opinion. For people living in a rural or remote area, 20% were supportive of further action, 78% were not supportive, and 2% had no opinion.

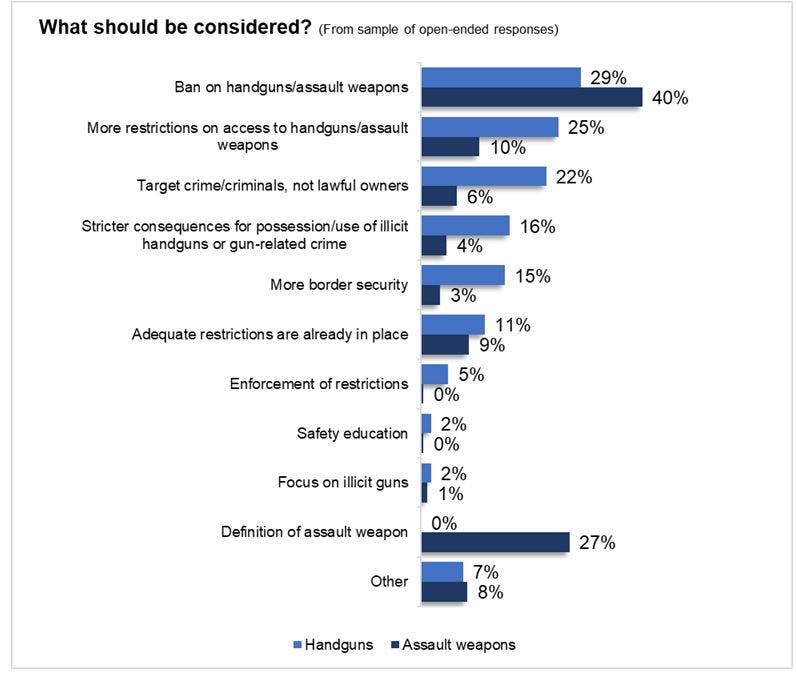

When asked what more should be done to limit access to handguns and assault-style firearms, respondents who answered the question suggested the following:

Image Description:

What should be considered?

An open-ended text response question asked respondents what action should be considered, with separate questions for handguns and assault style firearms. A sample of 1000 responses revealed the following themes.

- A ban on handguns/assault-style firearms (29% for handguns; 40% for assault style firearms)

- More restrictions on access to handguns/assault-style firearms (25% for handguns; 10% for assault style firearms)

- Target crime and criminals, not lawful owners (22% for handguns; 6% for assault style firearms)

- Stricter consequences for possession/use of illicit handguns or gun-related crime (16% for handguns; 4% for assault style firearms)

- More border security (15% for handguns; 3% for assault style firearms)

- Adequate restrictions are already in place (11% for handguns; 9% for assault style firearms)

- Better enforcements of the existing restrictions (5% for handguns)

- More safety education (2% for handguns)

- Focus on illicit firearms (2% for handguns; 1% for assault style firearms)

- Feedback on the term “assault weapon” (27% for assault-style firearms

- Other (7% for handguns; 8% for assault style firearms)

The top themes from responses on these questions include:

Ban on handguns/assault-style firearms: Some respondents called for a full/complete ban on handguns and/or assault-style firearms, with many suggesting there is no legitimate reason for the general public to possess either type of firearm. Subsequently, many noted law enforcement and military forces should be the only exception to the ban.

A few respondents favoured more of a partial ban, such as banning only semi-automatic firearms and assault-style firearms, or firearms currently classified as restricted and prohibited. Others suggested banning handguns only in urban centres/ within city limits.

“Ban them completely. I have seen no evidence that anyone except law enforcement persons has a need to own a handgun.”

“There is no justifiable reason for anyone aside from military and law enforcement to own assault weapons. Period.”

More restrictions on access to handguns/assault-style firearms: Some respondents identified the need for more restrictions on access to handguns and, to a lesser degree, assault-style firearms. Most call for a stricter, more extensive screening process. While some respondents provided only general comments, a variety of criteria and measures were suggested by others. Several respondents were concerned about the presence of mental health issues in individuals trying to acquire firearms, with some proposing that psychological or psychiatric evaluation, as well as social media checks (e.g., for hate messages) be incorporated into the screening process. Other screening considerations emphasized by some respondents include an individual’s criminal history (including individuals that are “known to police”), age, and reason/purpose for purchasing and using firearms.

“Certainly more extensive background checks.”

“Age, mental health, criminal background and reason for use or application.”

Additionally, some respondents suggested other restrictions or measures that could limit access for individuals, such as limiting the quantity of firearms that can be purchased (e.g., 1-2), lengthening waiting periods, only permitting use in rural areas or for hunting, requiring registration of firearms to purchase ammunition, and restricting the purchase of parts to PAL holders through registered shops to tackle illegal manufacturing of firearms. Other suggestions include additional enforcement and inspection capacity by authorities, such as through stricter storage requirements (e.g., only at gun clubs, providing evidence of compliance with storage requirements) and introducing regular check-ins with individuals possessing firearms.

Target criminals, not lawful owners: Several respondents disagreed that more should be done to limit access to handguns, emphasizing that criminals (especially gangs and organized crime) – and not law-abiding owners with legally acquired firearms – are the real problem. In their perspective, a ban would be ineffective because those who use firearms to commit crimes acquire them through the illicit market or through other criminal means and ignore licencing, storage and transportation requirements. As a result, many felt a ban unfairly punishes and criminalizes law-abiding firearms owners, and suggested greater focus on frontline law enforcement and border security to address smuggling from the U.S.

“Legal handguns and their owners are not responsible for 99% of gun crime. It’s the criminal element, primarily gangs.”

“Criminals do not go to stores to buy handguns… they are bought in the black market in back streets!”

Fewer respondents raised this theme when answering the question on limiting access to assault-style firearms.

Concern with “assault weapon” term: Some respondents did not suggest more limitations, but instead flagged strong concerns with the term “assault weapon,” which they felt is not clearly defined. As a result, most explained that the concept of a ban is problematic. Respondents suggested an assault weapon could be characterized by high-capacity magazines and/or the option for fully-automatic fire, characteristics which are already prohibited in Canada. Many expressed frustrations with the use of the term, suggesting that it is inaccurate and misleading (particularly with reference to the U.S. definition used in the engagement process). Some went further to suggest that the use of the term is sensationalist as it misrepresents the various applications of firearms. Additionally, a few respondents felt “assault weapon” is not a useful term because it can be used to describe a wide range of firearms/weapons (e.g., bolt rifle, bow and arrow), as well as any item that can be used to inflict harm on others.

“An assault rifle by definition requires select fire with a full-auto option. Full-autos have been banned since the ‘60’s, and magazine capacities above 5 rounds in semi-autos is already banned as well.”

The term “assault-style firearm” has since been adopted.

Some respondents also felt a ban is problematic because of inconsistencies in how certain firearms are treated. For example, some participants suggested that two semi-automatic rifles could have the same caliber round, magazine and fire rate, but one may be treated differently due to external factors, for example because it looks intimidating. Additionally, many firearms can be illegally modified with features that are already prohibited.

Other themes of responses to this question include:

- Stricter consequences for possession/use of illicit handguns or gun-related crime: Some respondents discussed the need for harsher penalties for criminals using illicit handguns or committing gun-related crime, such as longer jail sentences, establishing mandatory minimum sentences, not permitting sentence reductions or parole and imposing heavier fines. Some expressed dissatisfaction with current penalties, which they feel do not provide adequate deterrence.

- More border security: Some expressed concern with the smuggling of illicit firearms across the U.S. border and called for greater efforts to enhance border security, such as providing CBSA with more resources and tools to improve screening and search capacity and to establish stricter border controls.

- Adequate restrictions are already in place: Some respondents emphasized existing firearms laws are already sufficient (or according to some, already too restrictive) and that the licencing system works well because individuals are thoroughly screened. In their view, new restrictions are unnecessary and greater focus is needed on enforcing various aspects of existing firearms regulations, including screening, storage and sale. Some also expressed concern around the lack of broad public understanding of existing restrictions and suggested there is a need for more education.

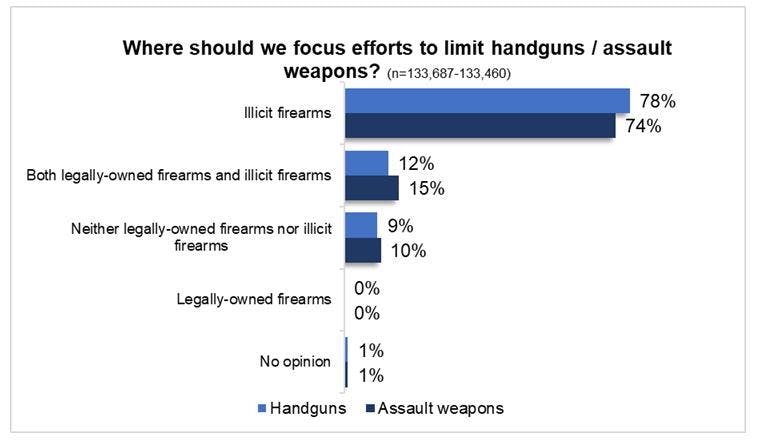

Views on illicit handguns and assault-style firearms

In the online questionnaire, participants were asked a series of questions to gather their views on illicit and legally-owned firearms. While questions were asked about handguns and assault-style firearms separately, similar responses were provided for both.

When asked whether efforts should focus on illicit and/or legally-owned handguns and assault-style firearms, most respondents wanted to focus on the illicit market. A small proportion called for greater focus on both and neither, while no participants suggested focusing solely on legally-owned firearms.

Image Description:

Where should we focus efforts to limit handguns / assault style firearms?

When asked whether efforts should focus on illicit and/or legally-owned handguns and assault-style firearms, the following responses were captured:

- Focus on the illicit market (78% for handguns; 74% for assault-style firearms)

- Focus on both legally-owned firearms and illicit firearm (12% for handguns; 15% for assault style firearms)

- Neither legally-owned firearms nor illicit firearms (9% for handguns; 10% for assault style firearms)

- Legally owned firearms (0% for both handguns and assault-style firearms)

- No opinion (1% for both handguns and assault-style firearms)

Respondents were then asked what is most likely to be effective and suggested the following, raising many similar themes as in previous questions.

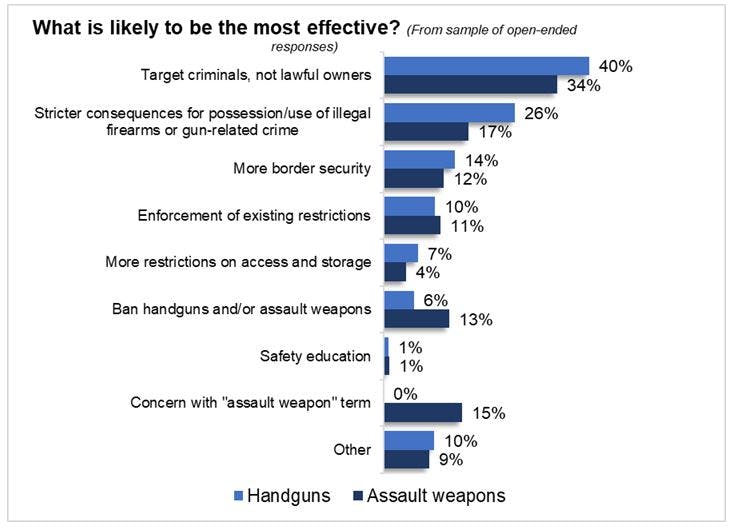

Image Description:

What measures are likely to be the most effective

An open-ended text response question asked respondents what measures are likely to be the most effective, with separate questions for handguns and assault style firearms. A sample of 1000 responses revealed the following of themes:

- Target criminals, not lawful owners (40% for handguns; 34% for assault-style firearms)

- Stricter consequences for possession/use of illegal firearms or gun-related crime (26% for handguns; 17% for assault style firearms)

- More border security (14% for handguns; 12% for assault style firearms)

- Better enforcements of the existing restrictions (10% for handguns; 11% for assault-style firearms)

- More restrictions on access and storage (7% for handguns; 4% for assault-style firearms)

- Ban handguns and/or assault-style firearms (6% for handguns; 13% for assault-style firearms)

- Safety education (1% for both handguns and assault-style firearms)

- Concern with “assault weapons” term (15% for assault-style firearms)

- Other (10% for handguns, 9% for assault-style firearms)

The questionnaire then focused specifically on the illicit firearms market, as respondents were asked to identify which source of firearms is of greatest concern. Most wanted efforts to focus on smuggling, followed by theft and straw purchasing.

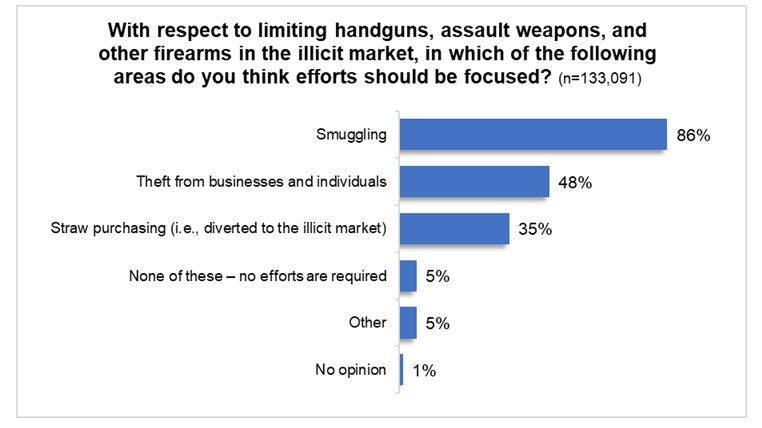

Image Description:

Where to focus efforts to limit firearms?

The questionnaire asked where efforts should be focused, with regards to limiting illicit and/or legally-owned handguns and assault-style firearms. 133,091 respondents answered this question.

- 86% of respondents suggested efforts should focus on smuggling.

- 48% of respondents suggested efforts should focus on theft from businesses and individuals.

- 35% of respondents suggested efforts should focus on straw purchasing (i.e. diverted to the illicit market).

- 5% of respondents suggested no efforts are required

- 5% of respondents suggested “Other”

- 1% had no opinion.

3.3.3 Data Collection and Analysis

The online questionnaire was hosted on Public Safety’s web platform, which collected all responses and exported both the summary and raw data in an Excel format for both quantitative and qualitative analysis for this report.

Quantitative Analysis

Both SPSS and Q research software were used to provide advanced quantitative analysis of the raw data from 134,917 questionnaires, specifically to identify and explore key trends based on respondents’ profile and demographic information.

As this was an open questionnaire process, no data weighting was done. Additionally, a margin of error could not be associated with the quantitative data.

Qualitative Analysis